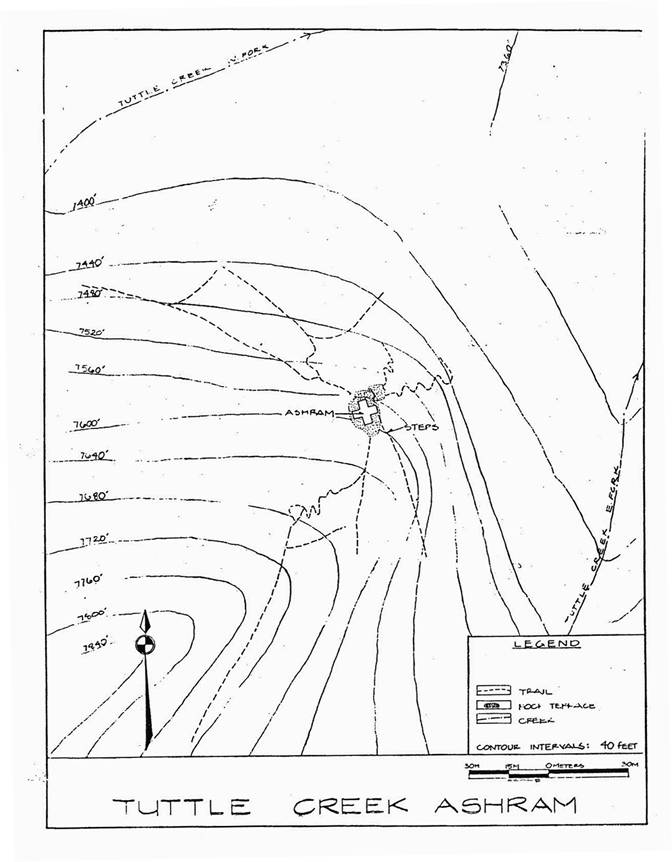

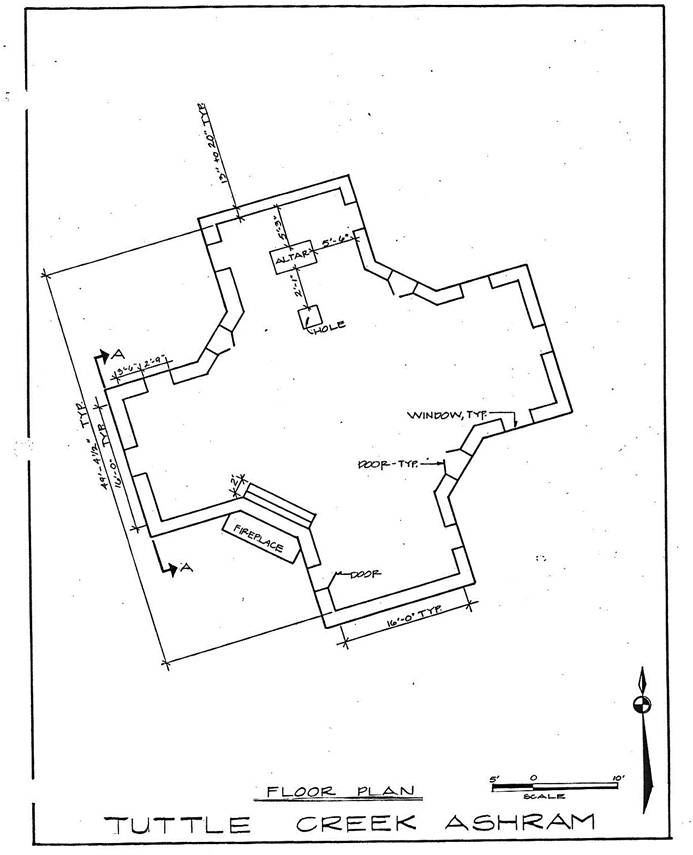

The Tuttle Creek Ashram is situated at an altitude of seventy-six-hundred feet on a steep ridge between the north and south forks of Tuttle Creek, a stream that flows briskly through a glacially carved canyon in the granitic Sierra Nevada Mountains.[1] Built in the shape of a balanced cross, the ashram is a two-thousand-square-foot structure of natural stone and concrete, with a cement floor, heavy-beam roof, and a large fireplace; the stonework of the ashram blends so well into the ridge that the building is hard to see even from a distance of one-half of a mile away.

The history of this remarkable building can be traced to 1929, when Franklin Merrell-Wolff and his wife Sherifa first visited the area west of Lone Pine, California. Here stands Mount Whitney, which at the time was the tallest peak in the United States.[2] The couple had been told by an Indian acquaintance that the spiritual center of a country was close to its highest point of elevation, and for this reason they sought a nearby location to work on several writing projects. Starting at the legendary Olivas Ranch, Wolff and his wife packed their typewriters and camping supplies onto burros and hiked up to Hunter Flat at the base of Mount Whitney.[3] The pair set up camp near a waterfall on Lone Pine Creek, and spent the next two months contemplating and writing.[4]

The history of this remarkable building can be traced to 1929, when Franklin Merrell-Wolff and his wife Sherifa first visited the area west of Lone Pine, California. Here stands Mount Whitney, which at the time was the tallest peak in the United States.[2] The couple had been told by an Indian acquaintance that the spiritual center of a country was close to its highest point of elevation, and for this reason they sought a nearby location to work on several writing projects. Starting at the legendary Olivas Ranch, Wolff and his wife packed their typewriters and camping supplies onto burros and hiked up to Hunter Flat at the base of Mount Whitney.[3] The pair set up camp near a waterfall on Lone Pine Creek, and spent the next two months contemplating and writing.[4]

The couple had recently founded the Assembly of Man, an educational organization with a generally theosophical orientation, and they decided that part of its work should include a summer school in the area they were camped. Wolff made inquiries to the U.S. Forest Service about a special use permit for the school, and was informed that in order to receive authorization for such an operation in the High Sierra Primitive Area, the Assembly would be obliged to erect some sort of permanent structure. Moreover, he was notified that building permits for the Hunter Flat area were not available. Accordingly, Wolff explored the next canyon south for a suitable site, and found a spot high in a beautiful piñon pine forest surrounded by two branches of a clear, cold creek. The founders of the Assembly of Man decided that the remote and quiet wilderness of Tuttle Creek Canyon would provide the ideal atmosphere for their summer school.

Wolff and the members of the Assembly of Man received permission from the Forest Service to operate a summer school on Tuttle Creek in 1930, but it would be almost ten years before a site was leveled for a structure. Wolff handled all of the dynamite used to blast a flat area, and as rock began piling up, he got the idea to use it in the construction of the building. The structure was laid out roughly along the four cardinal points of the compass, and built in the shape of a balanced cross to symbolize the principle of equilibrium.

Building materials such as lumber and cement were initially brought to the site on the backs of burros from Olivas Ranch, and the site was approached from the north side of the canyon. Later, Wolff cleared an access road on the south side of the canyon, which could accommodate a tractor pulling a flatbed trailer. Wolff and his students would spend twenty summers working on the ashram, spending their days engaged in hard labor and their evenings with music and study around a campfire. The group also held formal services at the site, with Wolff and Sherifa officiating. A large altar was constructed on the floor of the structure, using randomly patterned granite stones set in mortar; the altar was topped by a smooth covering of mortar. A 1940 film documents some the Ashrama construction (23 min) and the Assembly of Man “Convention” that year.

Building materials such as lumber and cement were initially brought to the site on the backs of burros from Olivas Ranch, and the site was approached from the north side of the canyon. Later, Wolff cleared an access road on the south side of the canyon, which could accommodate a tractor pulling a flatbed trailer. Wolff and his students would spend twenty summers working on the ashram, spending their days engaged in hard labor and their evenings with music and study around a campfire. The group also held formal services at the site, with Wolff and Sherifa officiating. A large altar was constructed on the floor of the structure, using randomly patterned granite stones set in mortar; the altar was topped by a smooth covering of mortar. A 1940 film documents some the Ashrama construction (23 min) and the Assembly of Man “Convention” that year.

Originally, there was no inscription on the altar, but sometime in the 1960s, an unknown visitor chiseled these words into the top face:

Just south of the altar, in the concrete floor, is a thirty-two inch square hole. This spot was called “the cornerstone,” and was where a person addressing the congregation was to stand. Over the years, the stonework walls, a large stone fireplace, two intersecting heavy-beamed gable roofs, and the window and door casings were all completed. But in 1951, before the windows and doors were installed, work ceased on the ashram because Sherifa, whom Wolff credits as being the main impetus behind the project, was no longer able to make the trip up to the building site. The name of the building was originally the “Ajna Ashrama”; today Wolff’s students refer to it simply as “The Ashrama.” Lone Pine residents often refer to it as “The Monastery” and one can find it called “The Stone House” in hiking guides; it is known by the U.S. Forest Service as the “Tuttle Creek Ashram.”

In 1964, the ashram was threatened with demolition when Congress passed the Wilderness Act, and Tuttle Creek Canyon became part of the John Muir Wilderness. Since the site had not been used as a school for over ten years, the Forest Service invoked a clause that allowed the agency to terminate Wolff’s special use permit. Moreover, since buildings are not typically permitted in Wilderness Areas, the Forest Service considered dynamiting the structure into rubble.

In the early 1980s, however, the Forest Service evaluated the ashram for historical significance, and concluded that the structure was indeed significant; the California State Historic Preservation Officer concurred. At the time, several video documentaries were made in an effort to help preserve the ashram: The Philosopher’s Stone (1980) and Ashrama Man (1983) are both available for viewing on the Franklin Merrell-Wolff Fellowship’s website.[5] In June 1998, the Inyo Register ran an article intimating that the ashram was in danger of demolition, but the Heritage Resources Program Manager at the local Forest Service office reiterated in the article that the ashram had been put on the removal list without any proper evaluation, and that “The Forest Service would be looking at preserving this . . . unique architectural property.”[6] Toward this end, it was planned to have the ashram nominated for recognition in the National Register of Historic Places, but these plans were never culminated; the topographical site plan and floor plan below are taken from the nomination form.

Endnotes

[1] Tuttle Creek descends from Mt. Langley (14,042 feet) to the town of Lone Pine, California.

[2] When Alaska was granted statehood in 1959, Mt. McKinley (Denali) became the highest point in the United States.

[3] Located at an altitude of eight-thousand feet, this area was also known as “Hunter Flat”; both names honored William L. Hunter, an early pioneer of Owens Valley and one of the two men who made the first ascent of nearby Mt. Williamson in 1884. (Mt. Williamson is the second highest peak in the Sierra Nevada Mountains.) The name of this area was changed to “Whitney Portal” after the official opening of an automobile road to the flat in June 1936.

[4] Wolff began writing his first book, which would be published under the title Yoga: Its Problems, Its Purpose, Its Technique; Sherifa drafted a Sanskrit dictionary called “Devanāgarī,” as well as several other essays.

[5] Faustin Bray & Brian Wallace, The Philosopher’s Stone (Mill Valley, Calif.: Sound Photosynthesis, 1980); Ashrama Man (Mammoth, Calif.: Mammoth TV, 1983). Both of these interviews may be accessed on the Interviews page under the Franklin Merrell-Wolff tab.

[6] Julian Lukins, “Efforts under way to preserve ashram,” Inyo Register, June 13, 1998.